Richard Feynman famously asked “What men are poets who can speak of Jupiter if he were a man, but if he is an immense spinning sphere of methane and ammonia must be silent?”

The answer is: We do not know how it is to be on an immense spinning sphere of methane and ammonia. Our homeworld, all too obviously, shapes our life -and thus our words, concepts, imagery. Culture makes a huge part, but after all we all live on the same celestial body, with the same atmosphere and physics. We know a rain made of water, falling out of grey clouds, that lets us think of (say) loneliness. We are serene under a blue, bright sky. We wake up wondering in the magic silence of gentle ice snow. We know our four seasons, all with their distinct character. We know one, little, pale moon.

We cannot apply this universal human experience to other worlds. Think of strolling under a Triton cryovolcano: a cold-beyond-belief mountain in a perpetual dusk, slowly slushing ice from cliffs of frozen nitrogen, while Neptune, blue and immense, perches in a black, slightly hazy sky. It makes perhaps us feel a sense of wonder, but we do not, we cannot associate it with a romantic scene, a childhood memory, a place we lived. The Earth poet cannot sing the clouds of Jupiter because our experience does not include them: and thus our language did not evolve to connect it to us.

For now. One remote day perhaps some of us will, indeed, live on other worlds. And these people will live new seasons, new landscapes, new colours. Couples will enjoy a weekend flying under the perpetual orange haze of Titan. Kids will wonder at the shiny brine of a Martian morning. A house could float under the continent-wide clouds of Jupiter. The eerie light of Saturn rings will bless lovers. It will be then that poetry, music, novels will include and flourish on these experiences and these memories. If one day we will have new worlds, we will also have new words.

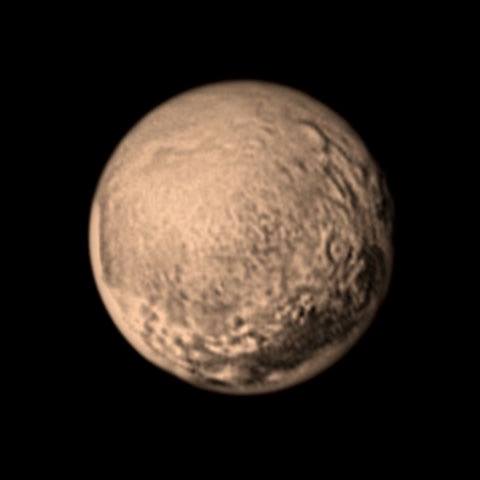

Pluto is close, and it looks so different, so unique, among the worlds we have known so far. In the previous post I argued that space exploration is more about us, about our experience, than about science. It might be a surprising attitude. After all, the science enthusiast is often disappointed that most layperson see a distant planet as a quirky distraction, as a somehow interesting news drowned in the minutiae of their own lives. The layperson is not guilty. They cannot really relate to Pluto: no heart ever broke on it. To understand the cosmos, to really describe it, we have to live within it, to make it the everyday mold of our experience. Until it is home.

Be First to Comment