“Oh, yes. I’m very proud of not having a Ph.D. I think the Ph.D. system is an abomination. It was invented as a system for educating German professors in the 19th century, and it works well under those conditions. It’s good for a very small number of people who are going to spend their lives being professors. But it has become now a kind of union card that you have to have in order to have a job, whether it’s being a professor or other things, and it’s quite inappropriate for that. It forces people to waste years and years of their lives sort of pretending to do research for which they’re not at all well-suited. In the end, they have this piece of paper which says they’re qualified, but it really doesn’t mean anything. The Ph.D. takes far too long and discourages women from becoming scientists, which I consider a great tragedy. So I have opposed it all my life without any success at all.”

(Freeman Dyson, from this interview)

I have a Ph.D. – actually, I have almost two Ph.D.s, one in experimental and one in computational molecular biology. The latter is to be discussed in the next weeks. I will not go into the (admittedly a bit self-contradictory) path that led me again into the Ph.D. rigmarole. But doing the experience a second time, with also some postdoc and industry experience in between, allowed me to see things with a modicum of detachment and clarity. This is what I concluded: The Ph.D., as an institution, is worse than useless. It is damaging, and it should be abolished. It hurts the professional recognition of early-career researchers, it fosters exploitation, it wastes valuable resources.

The Ph.D. devalues early academic career

Officially a Ph.D. is (in most cases) the finishing line on the track that brings you from the kindergarten to an actual job career. It is officially considered school: in fact, especially in US, it is called graduate school, and who is enrolled in a Ph.D. program is called a graduate student.

Problem is, “graduate students” are not students. They are workers.

The bulk of the graduate “school” is research work. Graduate “students”, in fact, are the main workhorses of modern research. It gives pause that a large percentage of modern science is actually generated by the hands and brains of young unexperienced or semi-experienced “students” (see here for example). A quintessential requirement for successfully completing graduate “school” is to have published at least a peer-reviewed paper as a main author. (By the way, this means that the most important intellectual endeavour of humankind is literally in the hands of inexperienced, underpaid, unrecognized trainees.)

Mind you: this is not part-time work, or even standard 9-to-5. It is hard, continuous work, with weekends and nights spent in the lab or writing research papers (see e.g. here). Journals advise graduate students to work most weekends and long hours, because that’s how you succeed. (After all, having a shitty job is a privilege! The abovelinked article tells it with a straight face: “Those who stick with a career in science do so because, despite the relatively poor pay, long hours and lack of security, it is all we want to do.”)

Granted, in some jurisdictions, most notably United States, graduate “students” also follow university courses, especially in the first couple of years. All of them are also studying somehow, sure thing: they read papers and books that allow them to do their job. So does a tenured professor. The job of research involves studying, but this does not make them full-time students. It makes them workers that need to learn things, as most qualified workers do.

It would be purely a matter of semantics if it wasn’t that the “graduate student” label actually damages the students,err,early career researchers. They have no employee status in many jurisdictions, which means in many cases no legal rights to paid holidays, parental leave, and so on. This results, among other things, in discrimination of women. And fixing this is hard: they are routinely denied collective bargaining rights. Also, the label “student” often implies, to some employers, that the time spent in graduate school was, er, school, not actual work -and the CVs are thus evaluated as such.

An even more worrying phenomenon is that of the unpaid graduate “student”. In many cases only a fraction of Ph.D. positions are funded: others are left unfunded, meaning that the “student” will receive no money (in fact, she will often pay a hefty tax) and probably will have to work to sustain her unpaid work. There is even a phenomenon of Ph.D. debt, people burdened by a 5- or 6-figures debt. For their privilege to work. Other times the Ph.D. is paid by doing academic chores, such as teaching. This is immensely valuable experience, but still, it is work that pays other -unpaid- work.

Sure thing, this does not happen in some jurisdictions/institutions, and others are joining the ranks of sanity, considering to regard graduate students as employees. But what is the point of this double status? Why the farce of considering them “students” when they are not, or they only are for a limited amount of their graduate time? The very fact that first world countries considers the bulk of their junior researchers as “students” is unsettling.

The Ph.D. allows for advisor abuse

All of your academic career is based on what happens during your Ph.D. It’s really a tribal thing: The real Ph.D. function is that of a rite of passage. If you hate your normal job, you are usually allowed to say “fuck this, I’m outta here” and look for another one. But you don’t have a normal job when you are a graduate “student”. You have to get through Rite of Passage, and the time and history of your Rite of Passage will be scrutinized. If you are late in it, or if you change it, you lose very valuable time, and you perhaps bring scandal. If you don’t have your Ph.D., no matter what, you cannot Climb The Ladder and become a postdoc, let alone a professor.

Any ritual has a priest officiating it. We call it The Advisor. If your advisor is a nice person, all is well. If not, you are in trouble. In some cases the advisor can decide when you graduate. You will need letters of recommendation from your advisor, and Gods forbid if they are less than stellar, let alone absent. The advisor holds the keys to the future.

We all know that absolute power corrupts absolutely, and unsurprisingly the higher education media are ripe with articles about grad school abuse. Even less surprisingly, this can take the form of sexual harassment, which is apparently rampant. Of course both of them happen frequently also at other levels of academia and in other jobs. Yet the unusual power hold by a graduate student advisor does not help. You do not report your advisor for harassment easily, knowing you will have to restart your Ph.D.

But also, the mere stress of knowing that the Ph.D. is a “make it or break it” proposition tends to be damaging. Ph.Ds. are extremely psychologically stressful and yet there is what has been called a “culture of acceptance” around mental health issues in academia. This is a Rite of Passage, so you have to show off how tough you are. If you break it under the pressure, too bad for you.

The thesis and viva make little sense

No one really agrees on the point of the Ph.D. viva. During the Ph.D, you should have proven your work’s worth by publishing on peer-reviewed journals. You should have learned to show it to the academic community by going to conferences. Then why going again through reviewers, presentation etc.?… Ah, right, the Rite of Passage. However, apart from honouring our hunterer-gatherer heritage, it looks like there is little reason for all the fuss.

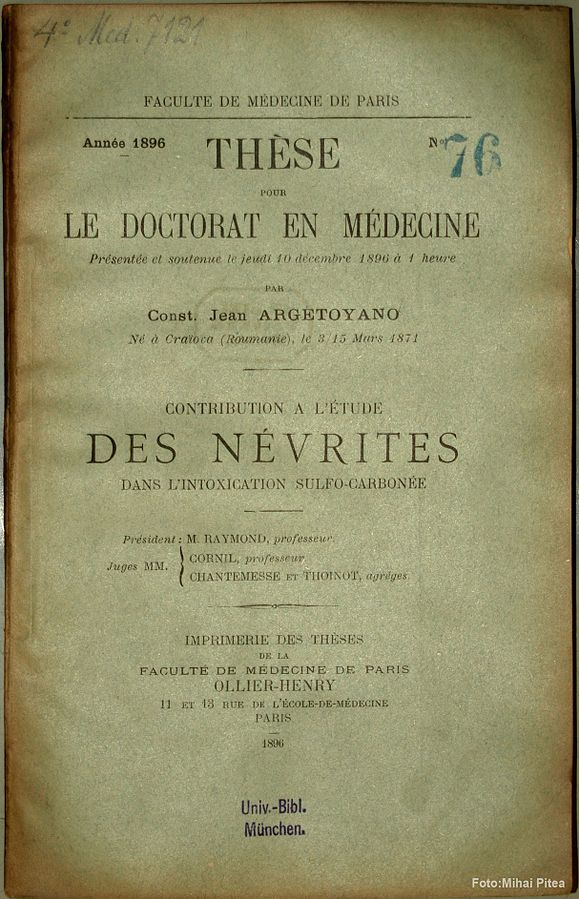

About the thesis, there is some reason to defend it (pun not intended). Condensing three years of work in a solid book is a worthwile exercise. It teaches something – I noticed you learn a lot of stuff anew when you write it in a thesis. For several types of disciplines far from my expertise, especially humanities, I am under the impression the (published) thesis is indeed actual academic currency. Even other paper-dominated fields such as STEM, in my opinion, should go back to the tradition of presenting or reviewing research in books, something that is today rarely done (The academic “books” published today in the STEM field are, almost always, either collections of paper-like disjointed chapters around a vaguely generic topic, or college manuals. Which is a disgrace.)

But then, you can always publish a book during your researcher work, without all the “student” charade and ceremonial roadblocks. For the STEM field, a thesis is academically worthless. What is in it, is already inside papers published or to be published, plus a review of the literature. Almost no one will read it after it has been defended. No one will care about it, alas – not even Ph.D. supervisors, often. Actual Ph.D. thesis are rushly written, redundant, often tragically boring review books: not really a good document of anything except “look mom, I can type 200 pages in LaTeX“. Whatever valuable experience a thesis is able to give, it is not worth the drawbacks of the charade. It is a waste of resources: for the “students” and for the committees. A minor one, perhaps, but still a waste.

What to do then?

There are too many Ph.Ds. There is a reason: it is a way to gather cheap, unprotected cannon fodder to fuel chronically underfunded academic research. The Ph.D limbo is the perfect way to perpetuate the current state of things. It is much harder to ask for commensurate pay when you are a “student”; it is much harder to ask for reasonable work treatment when you are a “student”. It lures you to think of what you are doing not as a real job, but as something that “will pay off later”, while you actually are cheap intellectual labour. Every discussion on how to reform Ph.D. is stuck until it is realized that who does research work is no longer a student. It is someone who produces knowledge.

It might make sense to have a (brief) further step in the academic ladder for who wants to enter academia. Specialization courses a bit like the first years of US Ph.D.s, teaching advanced research topics and covering skills typical of research work (how to read a paper, paper writing, networking, funding structure etc.) could bring people who want to enter research a better theoretical preparation, so that they do not just dive in cold water at the first run. We can call that a Ph.D, if we want, but it would probably make sense to just ditch the title altogether, since it would have little connection with the historical one.

From there, it should be regular research contracts. One could be worried that current postdoc contracts tend to be shorter than Ph.D.’s, and this insecurity would be dreadful for people entering research first, risking of never allowing them to build a reasonable research CV. It is a more than reasonable fear. But I surely do not think that abolishing the Ph.D. out of the blue, in a vacuum, would be the solution. It makes sense within a more general reform of the academic process. But it has to happen.

All good points. I am often surprised by how having a successful research track record — even one that is more extensive than most PhDs or post-docs — is not sufficient buy-in into the academy without a PhD. This is made doubly depressing when that buy-in is not even enforced by other researchers, but by administrators and bureaucrats who themselves are not academics. This negates the purpose that the PhD acquired in the early 20th century of professionalizing the industry under its own control. Because now we are under the control of administration.

A potential “up side” of student status that some might argue is in terms of immigration. From what I hear, it is easier to get a student visa to study for a PhD in the US than to compete in the lottery for the H1B. Although I guess the pessimistic interpretation of this is just that it allows the West to perpetuate neocolonializism by exploiting foreigners as cheap highly skilled grad “student” labour.

When querying about a PhD program, the professor sent a pre-written email with all sorts of interesting information. It included comments about knowing the difference between illegal and bad behavior. The professor stated that if something was not 100% illegal, you should suck it up and know that life is tough. Or else everyone will judge you for having thin skin.

I did NOT apply to that program. That attitude very much signaled a toxic work environment that allowed unethical behavior and harassment, as long as there wasn’t blatant proof of illegal activity. Sigh.

[…] a scientist on science […]